Interview with Piersandra di Matteo

12th June 2018

By Rossella Menna for Doppiozero

Translated from Italian by Konstancja Dunin-Wasowicz

In the midst of a reactionary wave, Atlas of Transitions stands as a timely project by involving all the elements that the so-called “real country” finds undesirable: Europe, migrants and many of the rights gained by a more or less advanced civilization. Trusting the potentiality of artistic practices to take on and even attack conservatism, populism and the immaterial streams of neoliberalism – where does this confidence come from? Is there a dangerous misunderstanding underlying a political and cultural discourse that brands otherness with the corporate trademark of a slick progressivism? What good is a slow-paced walk to us? Or a book made of cloth that sews together desires and secrets? Or an imaginary map of fantasies, in a world that is falling to pieces? What use is it to a boy whose destiny is uncertain and who lives on two euros a day? We talked about this with Piersandra Di Matteo, curator of Atlas of Transitions Biennale Right to the City.

Why does a discussion about migration begin with claiming the “Right to the City”?

I believe that no discourse on migration can avoid questioning the boundaries of citizenship, the right to live in a city, to flee and ask for shelter. The ten days of Right to the City arise directly from this reflection. The aim is to unpick the complex system of a city, along with its immaterial flows and cohesive urban meanings, by looking at them from a practical angle.

How?

First of all, by invoking the bodies that pass through it and the urban capacity to counter non-inclusive rulings through the use of embodied acts. Our call to action is intended to reclaim the city as a co-created space, where everybody has the right to become visible. The title of this 10-day event clearly refers to Henri Lefevbre’s 1968 Droit à la ville, but also draws inspiration from recent readings which reshape the idea of the city, within its new economic arrangements and productive systems dominated by globalised markets. Coming from an institution such as Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione and Arena del Sole Theatre – Bologna’s city theatre – the event is an attempt to exercise this right through artistic practices capable of generating new anthropological spaces. It thus entails making room for aesthetic universes and languages that are usually not found in such a venue. It means leaving the theatre’s premises, without simply and superficially moving to the outskirts, aimed at confronting the ways people project their lives. I would like to thank ERT Director Claudio Longhi for his total openness and also all the people who put great effort and enthusiasm into this event.

How did you give shape to this “oppositional stance” in terms of concrete planning?

We first thought about the social and institutional image of the figure of the migrant, seen as a needy subject asking for healing, that urgently needs to be deconstructed. Frequently, the integration schemes we so easily promote hide patronising behaviour. Instead of choosing performances with predefined forms and having migration as a common theme, we decided to invite a group of artists to think and rethink projects specifically designed for the city of Bologna. Preference was given to projects able to activate participative practices involving various kinds of inhabitants; locals, foreigners, students, migrants, asylum seekers, refugees, unaccompanied minors, all engaging in shared moments of imagination and need. The city thus becomes the protagonist of a project revolving around migrations, along with a mix of prohibitions, microclimates, taboos, rites of passage, stories of places and the value of usage. It isn’t about bringing the city onto the stage, but about testing its urban life and looking at its conflicts.

We worked on two principal axes, creating a dynamic relationship between the city center and its outskirts. The actions evolved between the Arena del Sole Theatre (its courtyard, hall and a new exhibition space created in the garage), and the areas of Croce del Biacco, San Vitale/San Donato, Piazza dei Colori, where the Mosque and Hub Mattei, the region’s biggest reception centre, are located.

‘Unleashing Ghosts from Urban Darkness’ Alessandro Carboni, photo by Enrico De Stavola

What does “creative attitude” mean?

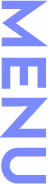

The city isn’t a “fact”, but a place to engage with. All the projects have the same aim – to map the city, walk through it collectively, redraw it on a human scale, and set foot in its potentially dangerous spaces. Anna Raimondo, for instance, worked on creating a transgeographic radio happening to question, thanks to the meeting with Carlos, Hamed, Moussa, Zaza, Lamil, Jasmine, Mazen, Naveed, the meaning of “being invisible” in the urban fabric. What does it mean to be an irregular immigrant or to have experienced such a condition? Valentina Medda worked with a group of women of various origins, who walked through disadvantaged areas to create maps in which perceived danger spots are erased by the mark of a ballpoint pen. In Vedute Prossime, all the installations belong to the mapping process. They are vocal, corporal, acoustic, visual maps, storytelling, actual tracks left following the participatory actions seen over the last few months.

Why is it so important to draw maps?

The maps we are trying to nurture are populated by bodies, as concrete urban experiences in which the unknown and desired faces of the city appear, leaving space for adventure and a collective creation that goes beyond the sum of its single projects. They are based on critical cartography and experimental geography, that have the power to question the border between legitimate and legal, real and imagined. This takes place in an in-between space, where the right to invention and reappropriation thrives as a key principle, fuelled by relations involving otherness and community.

‘Cities By Night_Bologna’ Valentina Medda

Do you believe performative practices can act on the urban fabric, going beyond the prefiguring influence of symbols and speeches?

Yes. I believe that certain performative practices designed as cross-cultural projects have an actual concrete power. I can say this because I’ve seen it happen in the last few months – and this was what was at stake in all of the processes activated. Here, I’m speaking of embodied practices. I wouldn’t underestimate the possible impact of giving visibility to such unpredictable figures and actions in public space. This can be translated into a real opportunity to express openness and actual participation. These practices represent singular gestures, that together form a constellation. Of course, it should happen continuously with the same energy. On the other hand, I think that a project about the arts, migrations and citizenship necessarily implies critical thinking, capable of reviving a series of politically informed questions within public debate.

Why is it the role of theatre to make this meeting happen?

Because a meeting requires bodily experience to act as an intermediary. In the performative practices we activated, the relation itself was always the most important element. While planning this project it was essential to meet the residents of reception centres, some of whom arrived very recently, deprived of everything and far from their families. Some of them are in a perpetual period of waiting for resettlement. The question is: why should they be interested in artistic work? Later on, the goal was to find a way to make theatre act effectively inviting citizens and newcomers to take part in a collective experience, on an equal basis. This doesn’t mean it was immediate or easy to achieve. We encountered many difficulties while working in magmatic environments far from the world of theatre, marked by profound cultural differences. Still, at the end, something happened.

Theatre generates real opportunities when it is real itself, one might say. But who or what can define the stringency in those potentially uncontrolled situations?

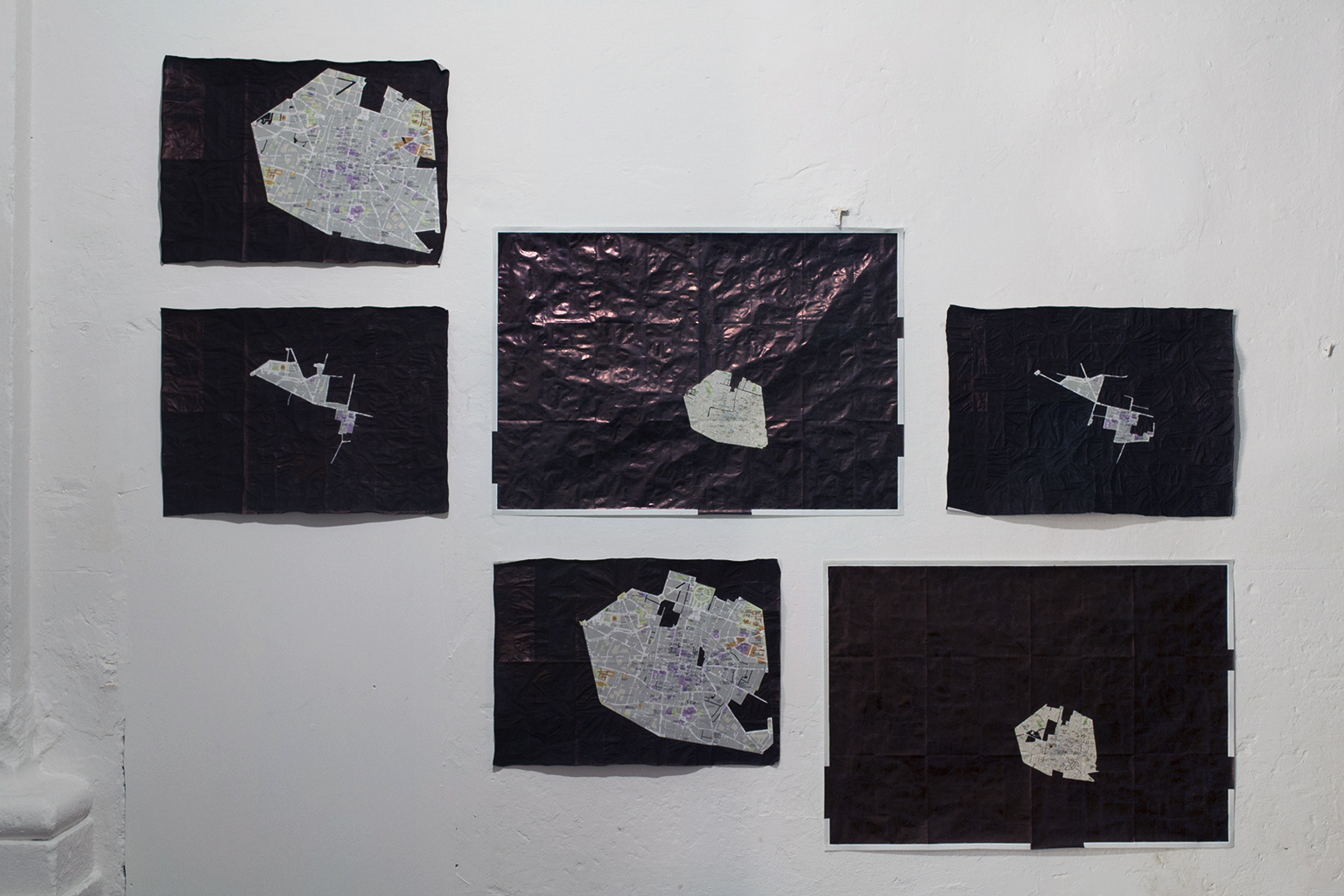

Rigour lies in choosing artists who have an elevated conception of artistic work, and who dedicate themselves to a radically processual art, making use of their human skills. In Alessandro Carboni’s work, Unleashing Ghosts from Urban Darkness, for instance, urban life, with its transformations, occurrences and accidents, becomes the ground material for a deeper observation. Here, the body is employed as a cartographic tool. Carboni designed a toolkit in eight languages based on the involvement of youths from Jordania, China, Romania, Hungary, Bangladesh, Brasil, Spain, Gambia and Italy, who realised a corporeal map of the city. The paradigm of translation, as Paul Ricoeur claimed, is also a form of “human to human” relations, in which otherness is given its full weight. Muna Mussie collaborated with women of different origins (Congo, Palestine, Nigeria, Russia, Argentina, China, Moldavia, Serbia, Cameroon) to compose and sew the cloth book, Punctuation together, using traditional embroidery techniques. The women met around the book and discussed the messages they would like to leave for the next generations. By casting it into the future, they exorcised their own taboos.

The experience that participants may encounter can be really deep. What does the audience actually experience in this process?

Anyone who participates in the various projects, even if not an expert of the given performative language, is asked to work with extreme seriousness. This has an effect on the aesthetic level and necessarily establishes an intense relation with spectators who have either travelled by choice to the various areas of the city or are randomly walking by.

Exactly. So it depends on the person. There is a risk that the work remains inert for those who aren’t embracing its premises.

Something could be ignited by the very chance that plural and perhaps confrontational discourses may be activated. People from various backgrounds take action and move through space, following a rhythm that differs from the one they are used to. Their gestures are intentional and politically informed. Obviously, this happens in a limited amount of space and time. Still, its effectiveness is multiplied a hundredfold, by each of the hundred people involved. The artists were called on to build an underground narrative based on dialogue, to bring out hidden desires.  Let’s take Memoria Esterna and Atlante for example, the workshops conducted by ZimmerFrei with a group of young people from Bologna, whether natives, adopted or transiting. The aim of the workshop is to realise a documentary film made up of various episodes entitled Saga. Zimmerfrei – Atlas of Transitions’ associated artists – led them through the act of observing, listening to various sites in the city, from the central bus station to a local market, from a small city square to the one behind the theatre. The artists took inspiration from An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (1974) by Georges Perec, who, seating at the table of a café, wrote down and described everything occurring around him. What are you watching from your perspective? What happens if you change it? And when you mix it with someone else’s? What do you see when you listen?

Let’s take Memoria Esterna and Atlante for example, the workshops conducted by ZimmerFrei with a group of young people from Bologna, whether natives, adopted or transiting. The aim of the workshop is to realise a documentary film made up of various episodes entitled Saga. Zimmerfrei – Atlas of Transitions’ associated artists – led them through the act of observing, listening to various sites in the city, from the central bus station to a local market, from a small city square to the one behind the theatre. The artists took inspiration from An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (1974) by Georges Perec, who, seating at the table of a café, wrote down and described everything occurring around him. What are you watching from your perspective? What happens if you change it? And when you mix it with someone else’s? What do you see when you listen?

Is there a vision of an ideal city that you pursue?

I imagine the future city as one that arises from a common project and guarantees the right to have rights. A city that acts as a shelter for anybody. The field of the arts is perhaps capable of testing this utopian vision. What I have in mind is a community-based process, in which people fight together and have a positive approach towards differences. Subjectivity should be intensified by diversity. Today, cities bear the signs of immaterial control and forms of securitisation that from the times of Fordism to the neoliberal era have taken on many different forms, which may be invisible but are no less coercive. The processes of gentrification and city branding make me worry quite a bit. Most of the time, this model of a city seems to be pacified by signs of participation, at least from a rhetorical point of view. However, convivial urban spaces that claim to be inclusive are often equivalent to forms of discrimination, because only those with the necessary economic means can have access to them.

‘Exil#17/Terra Rossa’ Collettivo Strasse, photo by Enrico De Stavola

Go to part 2/5